This post was originally published on Firstpost as Shouldering Scars: PTSD can Manifest in Mysterious Ways as this Author Found

__

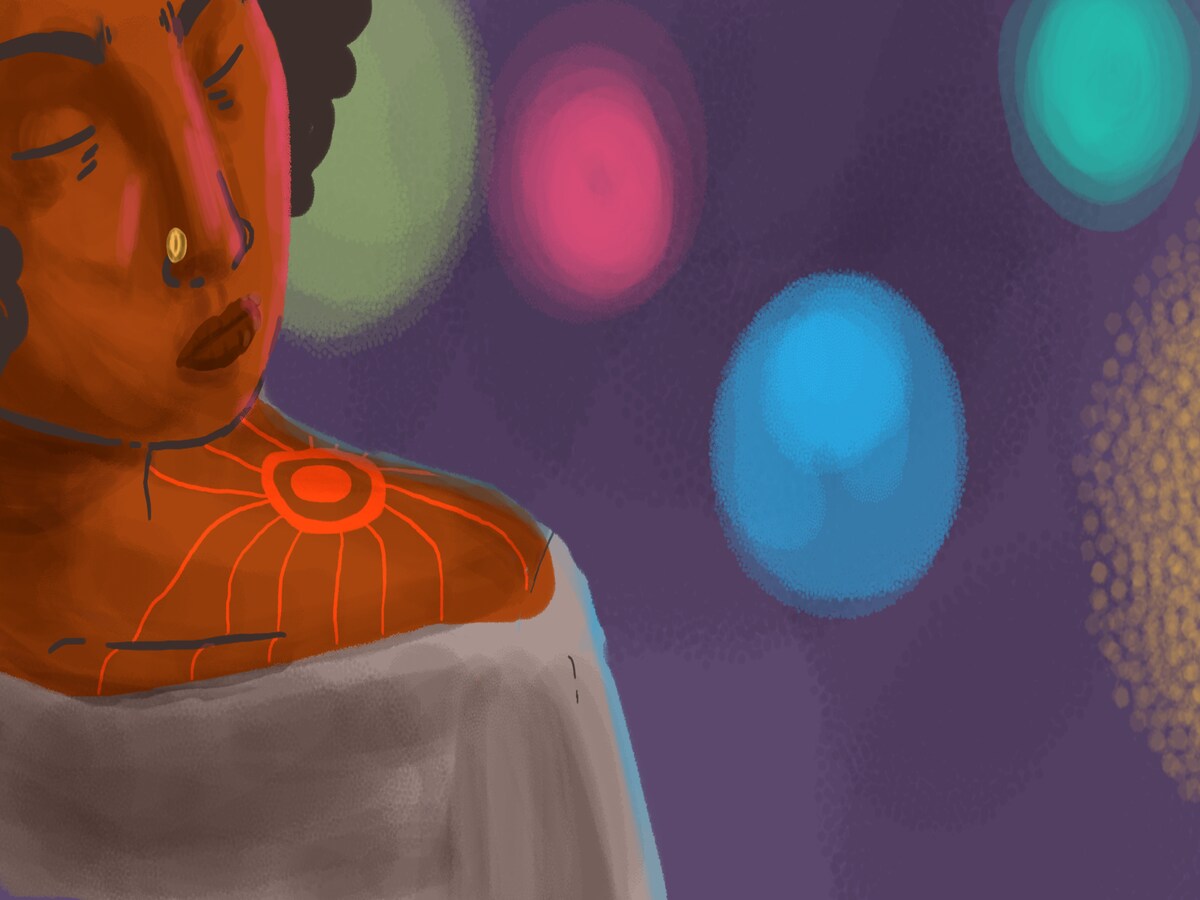

The sadness, said Van Gogh on his deathbed to whoever was listening, will last forever.* On both my shoulders I have red boil-like bumps. But they aren’t boils, they aren’t a curable infection. I know a boil when I see one. I have spent a life time bursting them, cleaning up the mess they leave behind.

My body is the repository of trauma and pain. I have always known this. In my years of being a writer I have realised that there is nothing better than a poem to explain the role physical ailments play in bringing the residues of that trauma, the pain, into our consciousness. It is why I open this essay with my poem ‘Souvenir’.

I start this poem with descriptions of the hideous scars on both my shoulders. Scars that showed up a few years ago and never went away. Whenever I went to see a dermatologist for them, the first question anyone asked was if I was in an accident. These bumps are trauma generated, they said. You know, if you injured your shoulders in an accident, gave yourself injuries, your body tried to fix them and gave you extra skin tissue while trying to do that. It seems it is your body’s tendency to generate extra skin tissue.

I mistrusted every single doctor with their uniform assessment of my malady because I had never been in any accident. There was no reason for my body to birth these scars. What was it rebelling against? What was it trying to say? Why this generosity of handing me extra skin tissue? As if I didn’t already have enough skin! The doctors, all three of them, informed me that I could fix them, but I would need to get injections. It always sounded too painful, way more than the ugliness resting on my shoulders. I never got the treatment because I wasn’t ready for needles poking through places that didn’t hurt. Aesthetics aren’t that important, I told myself and kept adding a bump a year to my shoulders.

In the beginning of May, I was in Munnar with a friend on a much needed and long-awaited vacation. After exhausting everything relevant — why we thought Priyanka Chopra deserved better than Nick Jonas, why we thought Karan Johar should meet us, why we love Shah Rukh, basically Bollywood, and some books, hers and mine and the ones we love and the ones we don’t — we moved to other things, like my sinking career, how I could fix it, and finally, our mental health. It was as we were discussing Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and how I may have added more traumas in my life to recover from, that I brought up these boils.

It wasn’t an epiphany (though I do wish — for dramatic effect — that it was). I had been thinking a lot about these random, unexplained presences on my body. The first one came up when I was miserable in a relationship that was not going anywhere, and I didn’t want to admit it much but was not making me happy. It was also the phase when my hypochondria and depression were at their peak. I was struggling with Trichotillomania and self-harming casually, even if not violently, by attacking already injured portions of my body with tweezers.

I was also in therapy then trying to stitch back the ripped pieces of my past into coherence so I could begin the healing, so I could start accepting the sexual violation I faced as a child. And simultaneous trying to mend my rapidly (albeit silently) declining relationship, whose fall I saw as a personal failing, one I was not ready to accept.

Growing up in a family that lost three of its daughters — my aunts — to cancer, I have heard a lot of talk about the side effects of trauma on the human body and how it degenerates the body’s capacity to hold together all that is precious. My aunts who passed away were all in unhappy marriages, or couldn’t bear children that they wanted more than anything. It was lifelong suffering, that we think took the shape of cancer. Today, we know that illnesses of all kinds are very much related to your mental health and your socio-political reality. So I am willing to believe that their personal tragedies made them more predisposed to these diseases.

While growing up, hiding myself from my past, and slowly but surely living through painful years of unrealised PTSD, I often fell ill, my stomach — always my stomach — taking the beating. When finishing my undergraduate degree, I was diagnosed with jaundice which was so borderline it might as well have not been there — and yet, I was throwing up every 10 minutes. The slightest of smells made me vomit. There was a stench I still haven’t managed to forget that haunted me for one long, neverending month, and that stench made me throw up. What was the smell that just wouldn’t leave? Where was that rot that I couldn’t stop smelling? Another time, on a wintry morning in January 2014, when I was admitted to the hospital after a marathon of loo runs at home, what was it that my body was pushing out? It wasn’t food, that much I knew.

If you can believe my therapist, and I do, I was vomiting and shitting my past. My stomach, she said, was a sieve, filtering out gradually all that I didn’t need. And if you trust Toni Morrison, as you should, she has said that anything dead coming back to life hurts. No wonder then I was hurting so much, all these times. I was, slowly over the course of many years post my tragedy, finally beginning to come back to life, the realisation of which also took a whole decade and more to happen.

In Munnar, I shared my investigations and findings with my writer friend Rheea, who has written a novel on the body’s — The Body Myth. What if, I said, these bumps on my shoulders are also indicative of my PTSD? What if these bumps showing up in the middle of a major life crisis indicate that my body is reacting to these invasions in the way it best can? That the trauma all the doctors have talked about is not physiological but psychological? She took a long drag of her cigarette contemplatively, and nodded in agreement. That has to be it, she said.

“You have been thinking from your stomach all your life. Your gut was your brain and so it was bearing the brunt of all your tragedies,” she asserted, and I agreed. My therapist had said the same thing, after all. But these bumps on my shoulders, what had changed with them? Why had my tragedies moved houses? Or perhaps they hadn’t. Perhaps they were just being redistributed so no one part felt burdened. If my gut has a brain of its own, so do my other body parts, right? There was no one particular thinking centre for me; each organ, each body part, doing what it knows is best for me.

Therefore, these bumps that I won’t let the doctors and their needles touch are a symptom of not just PTSD, but my body fighting it. My body is giving me this extra skin, extra padding so it can cushion all the blows my past — current and ancient — can throw my way. Like a symbol of all my fights, the ones I have won, the ones I haven’t even begun fighting. The poem I started this essay with ends in sadness, because it was written before this shift in perspective had happened.

What I don’t tell him

for he wouldn’t understand it anyway,

is that all his lotions and all his needles

are a temporary fix. Bumps will come and

go, but the sadness will last forever.

Now that I don’t think my bumps are a sign of my sorrow but a fight against it, perhaps I should write a new poem, countering the sadness in this one; rewrite my entire written history, as I do each passing day. Or keep this poem as a souvenir to remind myself that what feels like a lost battle is actually taking you closer to winning the war. And with PTSD, that is all that matters in the end.

Manjiri Indurkar writes from Jabalpur. Her forthcoming memoir on mental health, and a poetry collection called ‘Origami Aai’ will be published by Westland Publication in 2020 and 2021, respectively.